I focus on STM32 microprocessors in the discussion below, but the ideas could apply to any range of devices.

Background

I have spent a lot of time in recent years trawling through the datasheets, reference manuals and programming manuals for STM32 microprocessors. Mostly for STM32F4s, but also for STM32F0s. These documents are incredibly useful, and contain a wealth of information which is essential for correctly configuring and using the hardware. But there is a problem.

After the umpteenth time of looking up the DMA streams assignment table, I realised that what I really wanted for Christmas was all of that information to be available to me programmatically. I’ve made a couple of different attempts to capture this kind of data in a custom hardware abstraction layer, with all kinds of lookup tables and functions to access them. [Before you say it, one of the issues was that the firmware would waste a load of space on lookup tables and whatnot that are only used during initialisation.] This all worked pretty well, though it was far from complete, and I even got a chance to demonstrate some code to ST (Ans: C++? No thanks).

Writing these experimental libraries gave me a deeper insight: that what I really, really, REALLY wanted for Christmas was all of that information to be available in an easily accessible general purpose machine readable format. This would make it much easier to write productivity tools such as peripheral configurators, pin-out designers, clock tree setter-uppers, code generators, and any number of other things.

Writing such tools is burdened by the onerous task of compiling all of the required data across a range of potentially hundreds of devices with scores of variants. Unsurprisingly, it seems that only ST have risen to the challenge, and they have given us STM32CubeMX (see below).

So I started looking around for some detailed information sources that might satisfy my desire…

Possible information sources

SVD files

As things stand, we have SVD files. From what I can tell, they give enough hierarchical information about peripherals, their registers, and their fields, and their permitted values to allows a debugger to display the current values in the registers at run time. To be fair, I haven’t really dug into this: perhaps I’ve misunderstood. This page confirms my understanding: SVD format. That page mentions something called IP-XACT but, from what I can tell, that is not what I’m looking for.

From what I’ve seen, SVD files are of varying quality. They may or may not contain information about enumerated values for fields, for example. I’ve seen SVD files for virtually identical devices which nevertheless contained some odd discrepancies in register naming. There are almost certainly errors.

They also do not contain a ton of other useful information that is found in the datasheets. It appears that SVD files are aimed at a particular application (debugging), and contain just enough information to support that goal.

While it is possible to parse an SVD file to extract useful information (I’ve done this), I’m not convinced of the quality, correctness, consistency or completeness of that information.

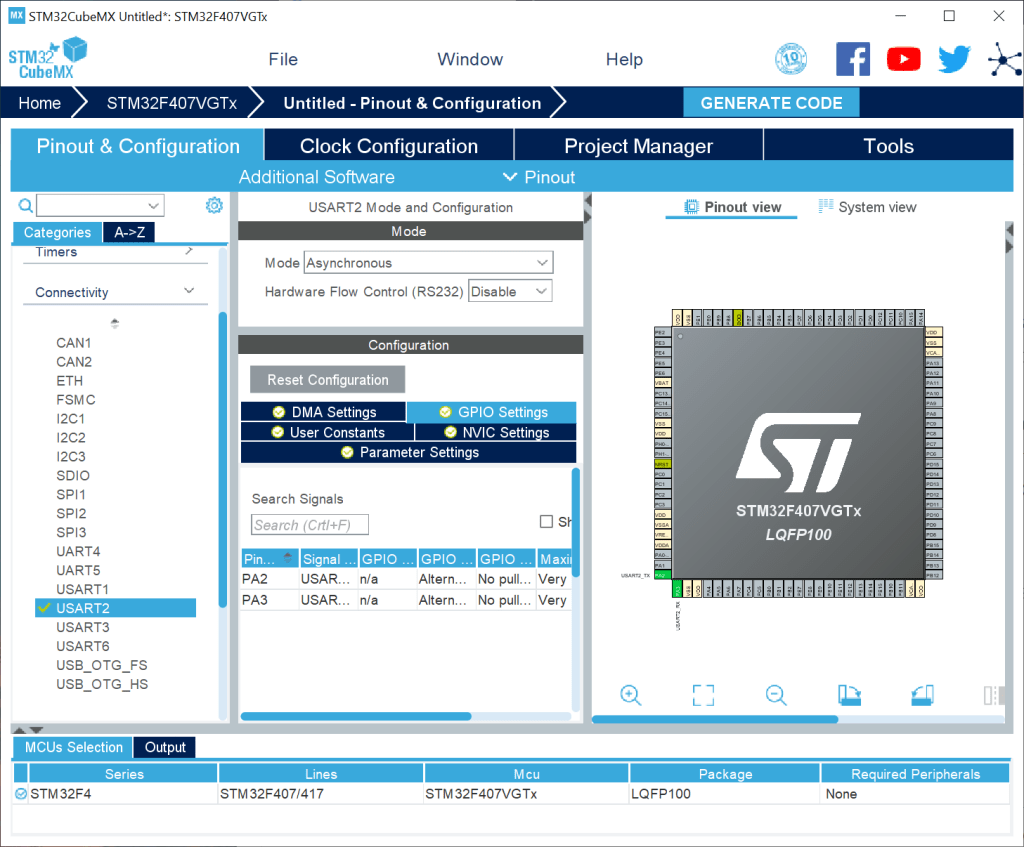

STM32CubeMX

ST have invested a great deal of effort in a hardware configuration tool called STM32CubeMX. It looks really good, and the GUI does a pretty nice job of helping you to configure the clock tree, pins, peripherals, DMA, interrupts and whatnot for your particular device. And it will generate the start up code for your project based on your configuration. As a former GUI designer myself, there is much about this tool that I think is excellent. It is certainly the best in this class of application that I have seen: nothing else seems to come close.

I just used it when getting this image. It’s been a while but my recollection was that the pins were easily changed to other valid options (through drop down lists). Not so, it seems. It took me ages to work out how to change from PA2 to PD5, and it wasn’t nearly as helpful as it might be – I had to hunt for the pin. Though it is a great start, I think CubeMX could be much better than it is, but that is a rant for another day.

I was curious about how the GUI knows which pins are acceptable for, say, SPI1 MOSI across hundreds of different devices. It turns out that it has a “database” of sorts. There are hundreds of XML files containing the necessary data. Unfortunately the format is not documented as far as I can tell, and the files appear to contain a lot of meta-data which seems to relate to the specifics of the GUI implementation in some way and/or to ST’s HAL library that CubeMX generates code for. It looks like a maintenance nightmare.

As with SVD files, while it is possible to parse at least some of the less obscure XML files to extract useful information (I did this), I’m not convinced of the quality, correctness, consistency or completeness of that information.

Time to roll my own

I decided to bite the bullet and create my own database. I won’t bore you with the details, but this entailed a lot of trawling through endless tables in the reference manual and the other resources already mentioned. The process was tedious beyond belief, and quite error prone. I captured the information in YAML, processed the YAML with a Python script, and ended up with a SQLite database containing everything I had gleaned from those sources. There was a certain amount of guesswork involved in creating the database schema because I have no inside knowledge about what the hardware designers were thinking.

The database is a self-contained general purpose information store about STM32F4 devices – a large subset of them, at any rate. The schema is published – or would be, if the database ever saw the light of day. The database is relatively easy to write SQL queries for. It could in principle be used by any other tool, written by any third party, in any language, and running on any platform.

What the database contains

The following list represents more or less what I captured in the database. There are sure to be some other useful nuggets I overlooked or didn’t need for the experiment. And then there are electrical characteristics, and, and, …

- For each particular chip variant covered by the database:

- RAM size, flash size, number of pins, physical package, maximum clock speed, and so on.

- Many variants contain exactly the same set of peripherals and whatnot, and I guessed there is a common die or something – same blob of silicon, but different packaging.

- A map of logical pins (e.g. PA2) to the physical locations on each package (e.g. Pin 27).

- For each distinct blob of silicon:

- The set of instances of peripherals it has: TIM1, TIM2, SPI3, USART7, and so on. This includes things like GPIOx, DMAx, NVIC, EXTI, RCC and other blocks which are perhaps not strictly speaking regarded as peripherals.

- Each peripheral can in a sense be regarded as an instance of a class. There are, for example, several different versions (classes) of the TIM peripherals, with various capabilities – these seem mostly to be subsets of some imaginary super-TIM.

- A whole family devices might use one class for SPI, say, which is very similar but not identical to the class used by another family.

- A given blob of silicon may contain a mixture of instances of different classes for each type of peripheral: TIM1 is nothing like TIM14, for example.

- For each instance of a peripheral class:

- The base address for its registers.

- Its interrupt sources and the map to interrupt vectors in NVIC.

- The set of bits and registers within RCC which are used to enable the peripheral.

- For each peripheral class:

- Its set of registers and their offsets from the instance base address.

- For each register: its set of fields and their sizes and offsets in bits.

- For each field: the type of data it contains (typically bool, int, or enum), whether it is read-only, write-only or whatever, and the range of permitted values.

- For each enum the names and values of the enumerators. In some cases several fields/registers will use the same enum, e.g. GPIO mode bits.

- For all of these things a description for human readers.

- The set of all interrupt vectors in NVIC:

- These are also part of the map to interrupts sources on particular peripheral instances.

- For the DMA peripherals:

- The set of streams and channels and how those are mapped to particular functions for particular peripheral instances.

- For each GPIO pin:

- The set of all alternate functions for each pin – which functions can be performed for which peripherals. This is quite a large table in the each datasheet.

- Details of the clock tree:

- All the different clock sources and their relationships through multiplexers, prescalers, enable bits and so on. That is, all the information required to draw the clock tree diagram which can be found in the documentation (and in the CubeMX GUI – it’s very pretty), and more.

- Which clocks relate to which peripherals, buses, RCC registers.

I am certain that my database schema could withstand a lot of improvement. I am also certain that my understanding of the internals of the various devices is flawed, and that the notional relationships I have invented to take advantage of apparent commonality between chips and peripherals is mistaken or misguided. I would love to get this stuff right. That would seem to require some input from ST’s digital hardware designers.

There is no rocket science in any of this. Just many hours of slogging my way through datasheets, parsing SVD and XML files. It really is not technically difficult but I have not found an existing resource like this anywhere. Perhaps I didn’t look hard enough. This seems very odd to me, because the nature of the data is absolutely begging for such treatment to allow users of these devices to exploit them more easily.

Example query

List all the pins which can be used for TX on USART2:

SELECT DISTINCT port.name, pin.pin_index

FROM GPIOPort port

JOIN GPIOPin pin ON pin.fk_gpio_port = port.pk

JOIN GPIOAltFunc af ON af.fk_gpio_pin = pin.pk

JOIN GPIOAltFuncType aft ON aft.pk = af.fk_gpio_af_type

JOIN PackagePin pack ON pack.gpio_name = pin.name

WHERE port.fk_gpio_class = 1 AND aft.name = 'USART_TX'

AND pack.fk_package = 1 AND af.instance in ('USART2')

ORDER BY port.name, pin.pin_index

It looks a bit complex, but isn’t really all that bad. There are tables for port, pin, alternate functions, types of alternate functions and a map from logical to physical pins (not all logical pins are exposed on smaller packages). These are joined and filtered with the name of the peripheral and the function we want. A couple of the foreign keys are numbers determined by the chip selection, but the bits for USART2 and USART_TX are clear.

I worked it out in SQLite Studio at first, and this one is generated in Python. In any case, end users would not normally be expected to write queries at all. Rather, this is the sort of thing that might be used internally by a configuration tool.

We could just as easily ask the database for all devices which match some specification (so many UARTs, so many SPIs, so much RAM, …), so that we can select the smallest for our project. Or for pin compatible devices. Or for all the different peripheral interrupt sources which share a given vector. Or…

A custom configuration tool

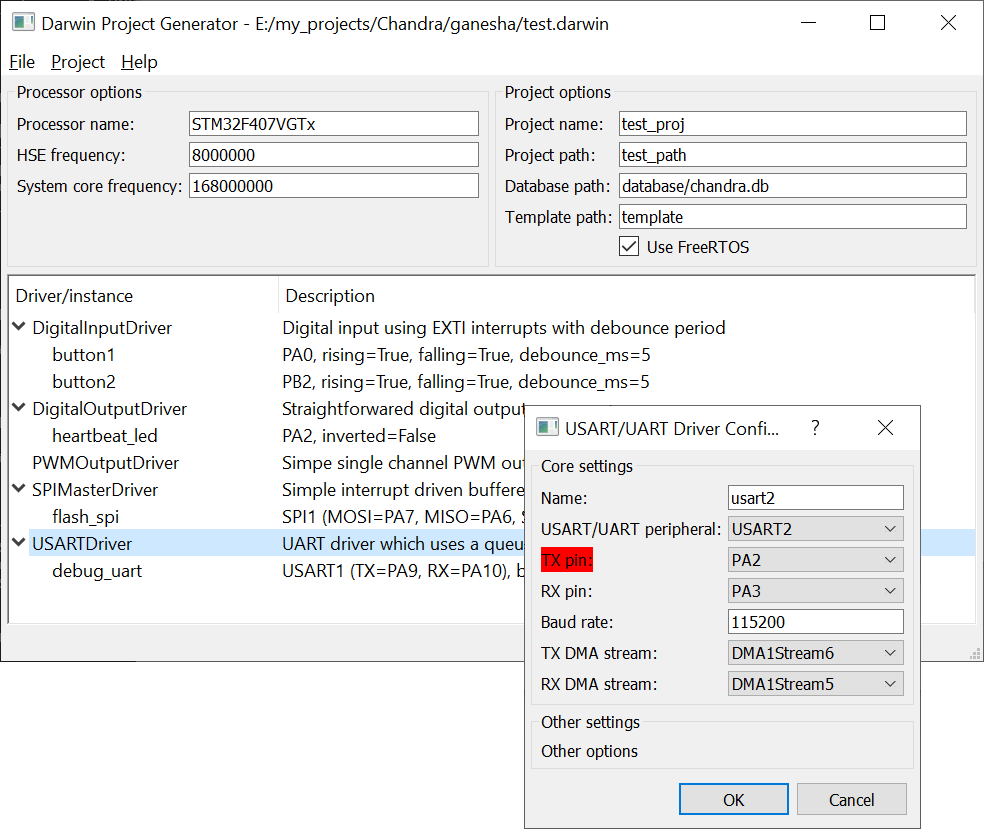

Imagine I am configuring a USART/UART driver in the tool shown below:

- The software already knows what particular STM32F4 I am using.

- I create a new instance of the driver USARTDriver from a menu of available driver classes. This is a GUI proxy for the actual USARTDriver class in my library.

- In the dialog that appears, I choose a UART/USART from a drop down list. The list contains only the peripherals that are available on the chip. It highlights the ones I have already used. I choose USART2.

- Now I choose a TX pin from a drop down list in the dialog. The list contains the results of the query above (PA2 and PD5, it turns out). It highlights a potential pin conflict: I have already used PA2 elsewhere in this case. Double assignment is permitted (you’re fine if the firmware serialises resource usage), but it’s good to know.

- And on to the RX pin, DMA streams, and other settings.

- The relevant DMA and USART interrupts are found automatically, as are the relevant RCC clock bits and other information that requires no user selection.

Of course, you will say that this is precisely what CubeMX does for us already. And you’d be right. Well sort of, I decided that a driver-level abstraction was better than CubeMX’s peripheral-level abstraction. And I generate code in C++ directly against my own library, which is not connected ST’s HAL. Later on I could update the tool to optionally generate Rust instead or, Heaven forfend, C.

This configuration tool is very far from complete – it’s just a toy really. I wrote it in Python as a demonstrator for the database. The point is that doing so was relatively straightforward.

A hardware abstraction layer

Creating a nice simple C++ HAL for STM32s has been something of a hobby horse of mine for a while. This whole database idea came up as an offshoot of that project.

If you have read Traits for wakeup pins, you may recall that I created a small compile time lookup table to help me not shoot myself in the foot with an invalid pin assignment on a Mighty Gecko. With a SQL database for this family of Silicon Labs devices such as I created for STM32F4s, it would be very simple to write a little script to generate exactly that table.

In fact, it would be simple to generate all kinds of tables to capture all kinds of information and relationships that would help to enforce correct combinations of pins, peripherals, functions, interrupt vectors and a dozen other things at compile time. At compile time! HALs usually contain hundreds or thousands of #defines for constants of various kinds, but little or nothing which explains their relationships or enforces any constraints on their use. Would it be good if the vendor-supplied HAL did those things? Personally, I think it would be awesome.

Generating some or all of the HAL

I would go further. Existing HALs contain a lot of duplication and/or conditional compilation. It’s wasteful and ugly and difficult to follow, and often depends on obscurantist preprocessor magic to select for your target device. But if creating big chunks of the HAL is a matter of running a script, why not do it for your specific project? That is to say, for your specific target device. Suppose the vendor supplied a script to do this. Or your could just write one yourself.

Such generated code would contain precisely the information you need, tailored to your particular device, and nothing more. It would be like having the datasheet in code form (derived from the datasheet in database form). Goodbye conditional compilation Hell.

And while we’re at it, why not also generate the SVD file your debugger needs for your particular device? Avoid filling up your hard disk with thousands of SDK files you will never use. 🙂

Testing for portability – sort of

Now suppose you have a fairly mature project and you decide you want to switch to a cheaper variant of the processor. Run the script to re-generate your HAL, build your project, see what won’t compile anymore. Oops! You used TIM14 and the cheaper device doesn’t even have it. Oops! You used PF7 and the smaller package doesn’t bring that out to a physical pin.

Go one step further: make the HAL generation a build step. Is this fantasy? Could it really be so straightforward? I believe it could. HAL code in C usually contains common functions across a whole family of devices. If your application is written in terms of a common API, but makes use of device-specific lookup tables for compile time configurations, then it should work.

There are, of course, no magic bullets. But I am absolutely certain that we could do a lot better in this area than we do currently.

A plea to microprocessor vendors

The pitch

I believe that ST and other vendors would be doing themselves and their users an enormous favour by creating such databases themselves. One for each family or sub-family of parts, say – whatever makes the most sense with their range(s) of hardware.

It seems obvious to me that the vendors already have at their disposal all of the information I want. And they already fully understand it and all the relationships within it which can be used to exploit commonality. To what extent their data is machine readable, I daren’t guess. However they do it, it is a fact that they produce enormous and generally accurate datasheets and reference manuals, which I suspect are something of a maintenance nightmare. What if all the tables in the datasheets could be created with automation which queries a database like mine? Just leaving that there.

Vendors also produce a great deal of code in the form of hardware abstraction libraries, board support packages, and the low-level ARM CMSIS stuff. It’s a sad truth that this code in always written in C, and is often of somewhat poor quality (hardware engineers should stick to what they know). To what extent the code is generated, I also dare not guess. Big chunks of it, with hundreds or thousands of macro constants, might be generated (CMSIS looks likely). There is a huge amount of duplication and/or conditional compilation. I dread to think what a maintenance headache that must be if it is all done by hand. It’s all a horrible mess, either way, and I am sure we could do better.

Finally, at least some vendors produce configuration tools and code generators which theoretically help users to get going on their projects. They don’t make money directly from their support code or their tooling. These represent a kind of loss leader intended to make their parts more accessible and thereby more attractive to developers. It seems to me that the burden of creating all that code and tooling must be quite heavy.

I believe that providing databases like the one I created (only more so) would be a powerful enabler for third parties, private projects, and the open source community. Creating tools is pretty straightforward. Obtaining the megabytes of data needed to make the tools useful is not. Enabling other motivated types to create tools and libraries could reduce the burden/expectation on the vendors, and (I’m getting carried a bit away here) might even help to increase the general quality of libraries and tooling in the embedded domain which, if we’re honest, is not really well served at the moment.

And finally… the plea

- To silicon vendors in general: Can we please make this happen? It could be amazing.

- To STMicroelectronics: Someone has to go first, right? I have ideas. Let’s talk.

How do I upvote?

LikeLike

Thanks. This idea has been bubbling around in my head for years, but I don’t have the detailed knowledge or resources to make it happen.

LikeLike